Your bank is selling your personal information. While the data is “anonymized” we recently revealed it’s scarily simple to re-identify subjects in data sets. So what gives? What information do your banks use, share and sell, and what are the privacy and cybersafety risks to you?

What are banks doing?

Banks have joined the masters of surveillance capitalism such as Google and Facebook in profiting from yourpersonal information. As Big Tech moves more into banking and financial services, banks are moving more into the data economy. Your credit and debit card activity and activity within loyalty programs are highly lucrative “data lakes”.

The motivation for the banks is profit, with a purported side order of customer service. It’s not surprising that banks would look to monetize their data sources at a time when bank earnings are under pressure. But this isn’t a new issue. At least a decade ago, banks realized they were sitting on a pot of gold of customer spending data, revealing where customers buy and how much they spend. They’ve since become increasingly adept at sharing or selling this data to affiliate partners and non-affiliate companies such as data brokers for marketing purposes. Those organizations either on-sell the information or tailor their own product-specific and location-specific deals based on the data insights, and the banks present the offers to their customers via text, email and other communications. The banks receive a commission for both displaying the offer and for processing the payment once the customer accepts it.

In fact, banks get a clearer picture of your personal information than most other organizations. Your bank is even better positioned than the Googles of this world to manipulate your spending choices because they don’t have to guess what you like from your search history—they have real information about where you shoppedand how much you spent. And what you bought today is usually a great predictor of what you will buy tomorrow so they can extrapolate valuable insights.

Of course, your banks don’t always know exactly what you bought, but they have solid information from which to guess in many cases. For example, your bank will know you shopped at Amazon but not that you bought shoes. But this can readily collapse and become more informative if you shopped at ‘Famous Footwear’ or ‘Christian Louboutin’ (clearly, you bought shoes). How much you spent is telling too: there’s a big difference between a $10 purchase and a $1000 purchase.

This author in Denver recently tracked his purchases of two bananas using two different cards to find out exactly who receives your data. He identified that a simple purchase at a variety store exposes purchasing data to:

- the store where you made the purchase, which shares your data with other companies who may use it to target ads and special offers to you

- the banks’ marketing partners who send you spam/junk mail

- other non-affiliates at the bank’s discretion

- co-branded card companies (e.g. Amazon gets information when you buy with the Amazon credit card)

- the card network (e.g. Visa or Mastercard) which gets the data, probably in anonymized form, andcould sell it to any other company

- point of sale systems and retailer banks, which get data when you swipe and can share it

- mobile wallets (e.g. Google Pay, Samsung Pay, Apple Pay)

- financial apps.

That’s a long list and, what’s more, banks’ data mining activities are becoming more sophisticated. Reuters recently pointed out: “Mining mountains of trading data to predict stock moves; partnering with retailers on marketing campaigns and using artificial intelligence (AI) tools to try and speed up credit decisions are some of the areas banks are focusing on.” They also report banks are spending big on business analytics and personnel (preferably recruited from a Big Tech company) to maximize the value of the data they collect.

What are the risks of all this data trading?

Historically, our relationship with our bank was a sacred one, much like the one we have with our medical professionals. We understood our bank knew some personal information about us but believed they used itlargely for fraud protection. Still today, we accept that we must trade some information in exchange for the financial services we use, but the challenge for us is that we don’t know exactly what data the banks are using and it’s incredibly difficult to opt out. By law, credit card companies must give us an opt-out option, but these don’t cover all the ways our bank might use our data. Complex forms, numbers to call, and long and complicated privacy policies deter many consumers from opting out—so the risks remain.

Of course, we might welcome some of the offers that are customized from our data insights, but there’s a fine line between convenience and invaded privacy and broken trust. In fact, levels of consumer trust for brands is generally low worldwide right now. Banks especially risk losing customer trust because the information they collect is highly sensitive. As we said earlier, banks can’t see exactly what we bought, but they can see the merchants, what types of merchants they are, the types of transactions and how much we spent. If the merchant has narrow scope (for example, it only sells shoes) it’s easier to infer the purchase. It might be more difficult when we buy from merchants that sell a variety of goods, such as Walmart, Target or Amazon. The frequency might also matter. For example, a customer who lives in San Diego but has an LA hotel booking every Wednesday night could be going for business, an extramarital affair or something else. But the pattern is part of what makes the transaction history interesting. And the very act of paying for the hotel means the customer is taking a trip and they might need car rental, travel insurance, luggage and so on, and soon ads for all this pop up.

Other important risks of bank surveillance capitalism are that customers who cannot afford the products on offer may be put at financial risk. What’s the duty of care here? And of course, any time our data changes hands it risks being stolen and abused. The more we interact in the digital space the more we risk cybercrimeand other abuse such as doxing.

What’s the law doing about it?

This use of data to sway customer spending decisions is exactly what recent regulations have moved to curtail. The GDPR and the CCPA, and particularly its successor, the California Privacy Rights Act 2020, aim to put the brakes on companies profiting from their customers’ personal information, but it’s a partial fix at best. Reuters recently commented: “… even with the extra protections, sensitive data is still at risk of being exploited because many people are not aware of how they can shield themselves. Less than a third of Europeans were aware of all their data rights and only 13 percent said they read privacy statements fully, according to a poll this year of 27,000 EU citizens.”

What can you do to protect your personal information?

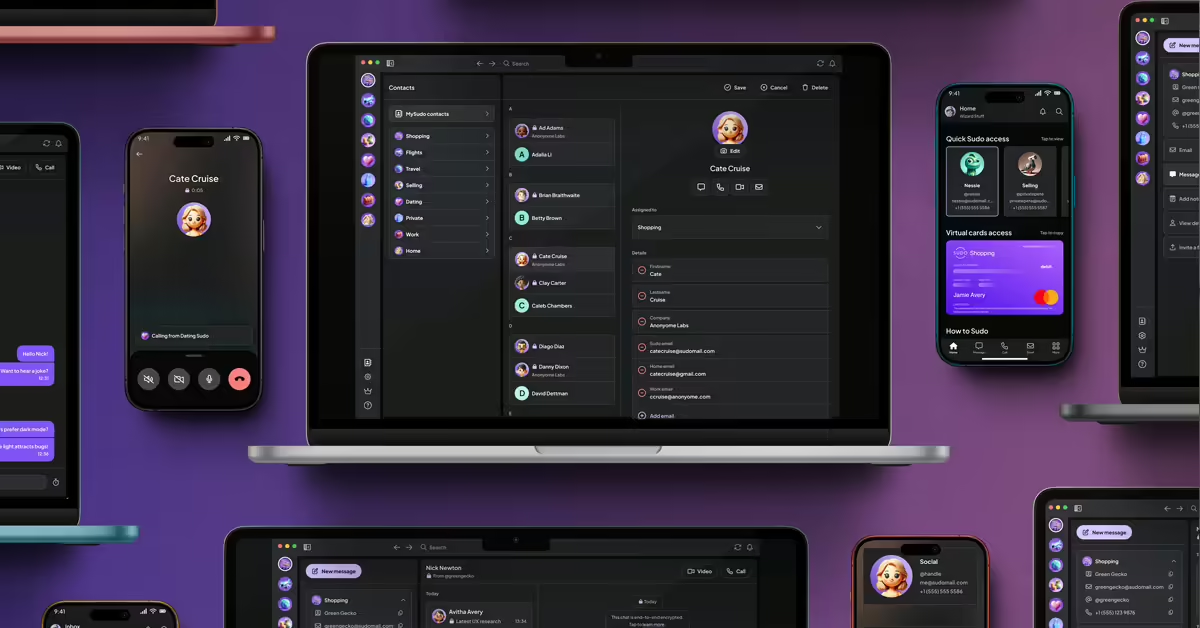

As with all questions of personal privacy, the answer is usually do your best with the tools and knowledge you have. At Anonyome Labs, we’re pleased to offer a real and powerful tool for significantly limiting the spending information you share with banks: MySudo virtual cards*.

A MySudo virtual card is like a financial avatar. It goes online in place of you and your personal credit or debit card and completes transactions without leaving your personal information. It protects your privacy and limits your financial risk. This means:

- You stay private online. MySudo virtual cards are not linked to your name, age, address, phone number, SSN, or any other identifying information, so your private data stays private.

- Your spending habits can’t be tracked. The charges you make with your MySudo virtual cards are simply described on your bank statement as ‘MySudo Transaction’. This means your spending habits can’t be tracked and so your data isn’t worth much to your bank or the data brokers.

- You reclaim control. MySudo gives you control over your personal information. Privacy matters, and at Anonyome Labs we don’t think being private should mean opting out of online services or hiding from the world. We empower you to be able to determine what information you share, and how, when, where and with whom you share it. This includes your financial details.

Find out why your MySudo virtual card is more private than a bank’s virtual card, or simply get started.

*This card is issued by Sutton Bank, Member FDIC, pursuant to license by MasterCard International. Card powered by Marqeta.