Identity is an important part of what it means to be human. People commonly believe they have a single, consistent, and unique identity that makes them who they are. They each have different values and experiences that they believe defines them.

In reality, identity is much more dynamic. People tailor their identity to different contexts, and how they interact with various groups, and who they are, changes over time. This feels quite natural in the offline world. When users go to work, the way they dress, their demeanor and the way they interact with colleagues is different from how they are at home with their family. When they gather at the dinner table with extended family, they might hold back on the political ideas and beliefs that would otherwise flow unfiltered when conversing with close friends. When they attend a conference and somebody asks for their phone number, they freely give them their work number but not their personal one, which is intimately tied to their personal life. They may therefore ‘re-invent’ themself at a new school or a new job, leaving behind some of their old self, only remembered by those who knew them then.

The Internet was built without an identity layer. We are now dealing with the consequences.

The Internet was not built with a functioning identity layer. Early in the Internet’s development phase, communication protocols concentrated on identities (addresses) for computers, to enable them to discover and communicate with each other.

Unfortunately, similar protocols were not created for identifying users. Instead, applications that operated across the network implemented their own identity protocols. For the past 30 years, the industry has tried various approaches to implement a usable identity service. Despite the emergence of authentication and authorization standards, such as OAuth and OpenID, most companies still leverage their own identity services for their consumers. As a result of this siloed ecosystem, users bear the burden of an unmanageable and complex system that includes widespread surveillance, identity theft, financial fraud, and the applications functioning as trojan horses for data exploitation.

The progress towards a reliable Internet identity service has occurred in two phases. The first phase is a centralized identity model whereby an application creates a unique service-specific account to identify each user. During account creation, an application commonly asks for a wide variety of personal user data, such as name, address, phone number, and email address. Under this system, a user is asked to authenticate to the application before they are granted access. If the user then wants to access another application, they must repeat the process, providing their personal user data again. In time, the user will have to manage hundreds of accounts, each with a copy of the user’s personal information, and each open to theft and exploitation.

Compounding the problem of managing so many accounts, users are also faced with maintaining secure passwords for each account. This is a serious problem, since most users re-use the same password for different accounts and/or create weak passwords that criminals can easily compromise. This pervasive problem exists because strong passwords require additional effort, such as using password managers.

To overcome the need for users to manage hundreds of separate accounts, the second phase of Internet identity was widely adopted, known as the federated identity model. Using protocols like SAML, OAuth and OpenID Connect, a user is identified on a trusted third-party identity service (e.g. Facebook), and this identification is re-used to access other services (e.g. Spotify). The premise behind this paradigm is that if both the user and an application each trust a third party, then an application is willing to create an account and allow subsequent logins when the user provides credentials from the third party. This type of model is also called social login (e.g., login with Facebook), and is familiar to individuals with Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, Apple, and similar accounts. Although more manageable for a user who does not have to remember passwords for each individual account, this paradigm comes at a high privacy cost, since the third-party identity service is able to track interactions with applications the user accesses with the social login. In addition, if the third-party service is compromised, it could compromise all the applications that used the third-party service.

Another related problem is applications’ misuse of a user’s personal identity. Most Internet users have been issued a legal identity by their government (e.g. passport, drivers’ license). These identities are intended to be used in a limited set of circumstances where precise validation of a user’s identity is required (e.g. flying on a plane, opening a bank account, etc.). A personal identity then is an extension of this legal identity where other personal attributes are also included e.g. personal mobile phone number, personal email address, home address, IP address, credit cards numbers and so on.

In reality, these personal identities are dangerously overused. Whether in the centralized or federated identity models, users are typically required to use their personal identity. This is an unwanted and unnecessary use of the personal identity that is fraught with serious privacy risks. One risk is that using a personal identity will establish highly correlatable reference data. A more serious risk is that most of the attributes of one’s personal identity are difficult to change, leaving the identity holder little recourse in the event of abuse, such as identity theft. A person may need to spend thousands of dollars and many hours trying to fix the damage caused by the abuse.

The combination of these poor identity models and the overuse of the personal identity has left users in a very risky situation.

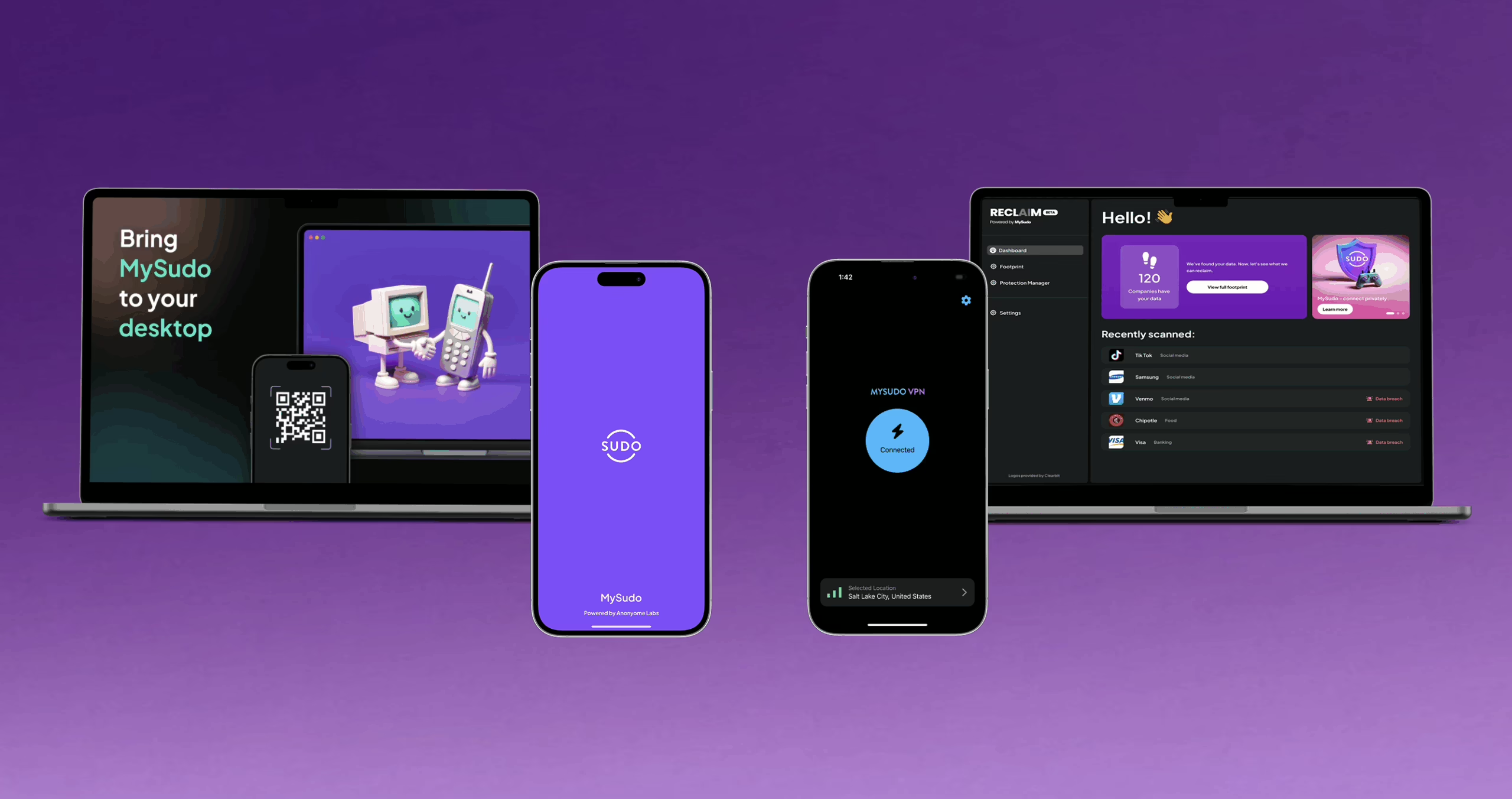

Find out how Anonyome Labs’ secure digital identity, known as Sudo, can help you mitigate these very real risks.